A couple of weeks ago Antiques Roadshow on PBS aired an episode entitled “Celebrating Native American Heritage.” It was a compilation of appraisals from previous shows highlighting art and artifacts from Indigenous creators and history makers. An item of particular interest to me was a 1933 handwritten letter from legendary athlete Jim Thorpe.

The letter was interesting, especially one passage in which Thorpe wrote, “If I can only get it, I have 1,250 bucks coming now in this year’s salary but seems rather hard to get–that is from the owner.” Antiques Roadshow originally appraised the letter as being worth $5,000 in 2017, and on this recent episode, they increased the appraisal to $6,000.

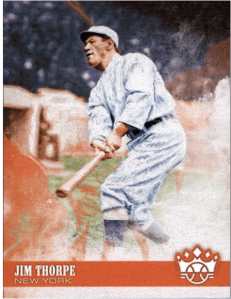

Many consider Thorpe the greatest athlete of the twentieth century. An American Indian, he was born on the Sac and Fox reservation in Oklahoma in 1888. Thorpe attended Carlisle Indian School in Carlisle, Pennsylvania, where he excelled as a college football player. He was a first-team All-American in both 1911 and 1912. In the 1912 season, Thorpe scored 25 touchdowns and 198 points, leading his team to a 12-1-1 record.

In the summer of 1912, he represented the United States at the fifth modern Olympics, held that year in Stockholm, Sweden. He won both the pentathlon and decathlon, setting records that stood for years. When presenting Thorpe with his two gold medals, King Gustav V of Sweden told him, “You, sir, are the greatest athlete in the world.”

Unfortunately, Thorpe did not get to keep his gold medals for very long. A Massachusetts newspaper reported that Thorpe played semiprofessional baseball in the Eastern Carolina League in 1909 and 1910. After Thorpe admitted to accepting $25 a week to play for the team in Rocky Mount, the American Olympic Committee stripped him of his gold medals and struck his name from the Olympic record books.

It was common at the time for college athletes to play semiprofessional baseball under assumed names in order to make some extra money; Thorpe played under his own name.Thorpe claimed that he was unaware that he was in violation of the rule against professionals participating in the Olympics.

The Olympic Committee supposedly was a stickler for the rules. They said that ignorance wasn’t an excuse, and it is difficult to argue with that stance. However, Thorpe’s violation was not discovered until six months after the Olympics, well past the 60-day deadline for filing a letter of opposition, according to the rules of the Committee. So, it seems that the American Olympic Committee held the line on one rule while completely ignoring another one.

While baseball cost Thorpe his amateur status and he eventually played six seasons in the major leagues, his greatest success was on the gridiron. He was a member of the inaugural class of inductees into the Pro Football Hall of Fame in 1963.

If there is a hero in Thorpe’s story, it may be Ferdinand Bie of Norway. He refused to accept the gold medal for the pentathlon after they took it from Thorpe. Hugo Wieslander of Sweden received the gold medal for the decathlon and reportedly felt uncomfortable about keeping it. Uncomfortable or not, he hung onto it until 1951 before donating it to a sports museum in Sweden.

In 1982, nearly 30 years after Thorpe’s death, the International Olympic Committee gave his family duplicate medals, but still only listed him as co-champion in the record books. It wasn’t until July 15, 2022, the 110th anniversary of him winning his gold medals, that the IOC reinstated Thorpe as the sole winner of the 1912 Olympic decathlon and pentathlon.

Leave a comment