I do not submit this post as a criticism of Billy Wagner, the longtime relief pitcher recently voted into the Baseball Hall of Fame. I do however, propose this week’s musings as a criticism of the save, which is the one stat that accounts for Wagner’s enshrinement into the hallowed halls of Cooperstown.

Wagner was a steady performer for 15 seasons, mostly with the Houston Astros. He has 422 saves on his ledger, eighth most in major league history.

Of the seven pitchers with more saves than Wagner, three–Mariano Rivera, Trevor Hoffman, and Lee Smith–are in the Hall of Fame. Kenley Jansen and Craig Kimbrel were active in 2024, and Francisco Rodríguez received 10.2% of the vote in 2025, his third year on the ballot. John Franco, who had two more saves than Wagner, did not receive the minimum five percent of votes required to remain on the ballot in 2011, his first year of eligibility.

There are six pitchers with far fewer saves than Wagner in the Hall of Fame: Dennis Eckersley, Rollie Fingers, Bruce Sutter, Rich Gossage, Hoyt Wilhelm, and John Smoltz. Eckersley and Smoltz are outliers, as they also were excellent starting pitchers for substantial portions of their careers.

The save and the terminology for the pitchers who accumulate them have evolved over the years. When I first started following baseball, a save went to the relief pitcher who finished a game his team eventually won, and another pitcher got credit for the win. The score at the time the pitcher entered the game was not a factor.

Beginning in 1975, to earn a save a pitcher had to finish a game his team eventually won after having entered the game with his team leading by three or fewer runs, or with the tying run on the bases, at the plate, or in the on-deck circle, and another pitcher got credit for the win.

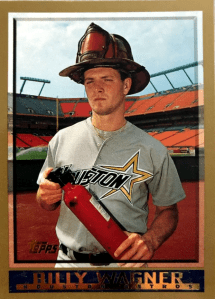

Broadcasters and writers informally used the term save for years before it became an official statistic. They reserved the terminology for a pitcher whom they felt actually saved the game. In its earliest iteration, they attached a save to a pitcher who entered the game and successfully bailed the previous pitcher out of a jam and then remained in the game until the end. They also referred to these pitchers as firemen. That concept of a save fits very well with the manner in which Sutter, Gossage, Fingers, and Wilhelm, accumulated most of their saves.

In today’s game, most saves go to pitchers who enter the game at the beginning of the ninth inning and blow away the opposing hitters with fastballs of around 100 miles per hour. Since there usually is no fire for such relief pitchers to put out, the firemen of years ago have become closers.

Rivera is the all-time leader in saves with 652, but he isn’t in the top 10 when it comes to saves in which he pitched more than one inning. Fingers holds the top spot in that category with 201, which is 58.9% of his career total of 341. Mike Marshall, an early relief specialist, had just 188 saves in his career, but he pitched more than one inning in 127 (67.5%) of them. Rivera had only 119 such saves (18.3%), and Wagner had only 36 (8.5%).

Don’t get me wrong; Billy Wagner was a fine pitcher. But he only twice led the league in any statistical category–games finished in 2003 and 2007. I’m just not sure piling up a lot of modern-day saves is enough to merit a call from Cooperstown.

(All statistics are from Baseball Reference and Retrosheet. For a deeper dive into saves, check out the article All Saves are Not Created Equal by Gabriel Schecnter from SABR’s 2006 Research Journal.)

Leave a reply to Gary Trujillo Cancel reply