I find myself increasingly frustrated by wins above replacement, the newfangled baseball statistic commonly known as WAR. Commentators toss around WAR as if it is the definitive measure of a player’s production. Baseball Reference puts WAR in the first column of each player’s stats on their website. But unlike traditional stats such as batting average, on-base percentage, and slugging percentage, WAR is a concept based largely on subjective criteria masquerading as data.

The definition of WAR doesn’t clarify much for me. According to MLB.com, “WAR measures a player’s value in all facets of the game by deciphering how many more wins he’s worth than a replacement-level player at his same position (e.g., a Minor League replacement or a readily available fill-in free agent).”

MLB.com goes on to define the formula for determining a player’s WAR, but that formula is full of abstract concepts like an adjustment for league and the number of runs provided by a replacement-level player. Who are these mythical replacement players and how does one determine how many runs they would provide?

I understand that we shouldn’t use any one statistic as a definitive measure of who is most valuable to a team or league. Batting average tells part of the story, on-base percentage tells us a little more, and adding those two stats together (on-base plus slugging percentage or OPS) gives us still another metric. What I like about these stats is that, unlike WAR, you apply actual data to an established mathematical formula to produce the final result.

I concede that WAR is another beneficial data point for determining a player’s value; however, given its definition it is absurd to use WAR when comparing players at different positions. MLB.com seems to make this same point by saying, “For example, if a shortstop and a first baseman offer the same overall production (on offense, defense and the basepaths), the shortstop will have a better WAR because his position sees a lower level of production from replacement-level players.”

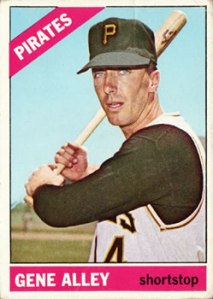

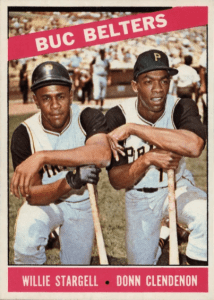

I never gave much thought to WAR until I noticed a line of photos labeled “Top 12 Players” at the top of Baseball Reference’s page for the 1966 Pittsburgh Pirates. Roberto Clemente is in the first position, and no thinking person would argue with that. However, numbers 2-6 are Gene Alley, Willie Stargell, Bob Veale, Donn Clendenon, and Matty Alou.

Using WAR, we are to believe that Alley was more valuable to the Pirates in 1966 than were Stargell, Veale, Clendenon, and Alou. Alley had a great year in ‘66; he hit .299 with seven home runs, 43 runs batted in, 28 doubles, and 10 triples. Alley’s WAR was 5.3 compared to Stargell’s 4.8, but that doesn’t convince me that Alley was more valuable to the Bucs than was Stargell, who hit .315 with 33 homers and 102 RBIs; the same goes for Clendenon and Alou. (I left out Veale because it is especially absurd to use WAR to compare pitchers and position players.)

Defense also figures into WAR, but other than fielding percentage, it always has been difficult to put a number value on defense; therefore, any defensive measures factored into WAR only increase the subjective nature of the final metric.

Part of my love of baseball comes from real numbers. I love it that when Henry Aaron got 164 hits in 547 at-bats, and Barry Bonnell got 108 hits in 360 at-bats, and Mike McQueen got six hits in 20 at-bats, they all were .300 hitters.

I’m all for new metrics. I just want them to be based on real data and then applied appropriately when comparing players.

(All statistics are from Baseball Reference.)

Leave a reply to Gary Trujillo Cancel reply